Starting with Event Sourcing

To many developers, event sourcing is a magical beast that's used to build extremely complex, often distributed projects. And there's good reason for that: event sourcing is a pattern that forces code to be built in a way that fits those complex projects exceptionally well.

Words like “modularized”, “distributed”, “scalable” and “versatile” come to mind to describe it; characteristics you can't do without if you're building applications at scale. Think about a popular webshop or a bank, handling maybe thousands if not millions of transactions per second. Those are the kinds of projects event sourcing most often is associated with.

And thus, event sourcing is rarely every used in smaller projects, the ones many developers deal with, the ones many of my regular blog readers work on.

I think the reason for this, is because of a fundamental mistake of what we think event sourcing is.

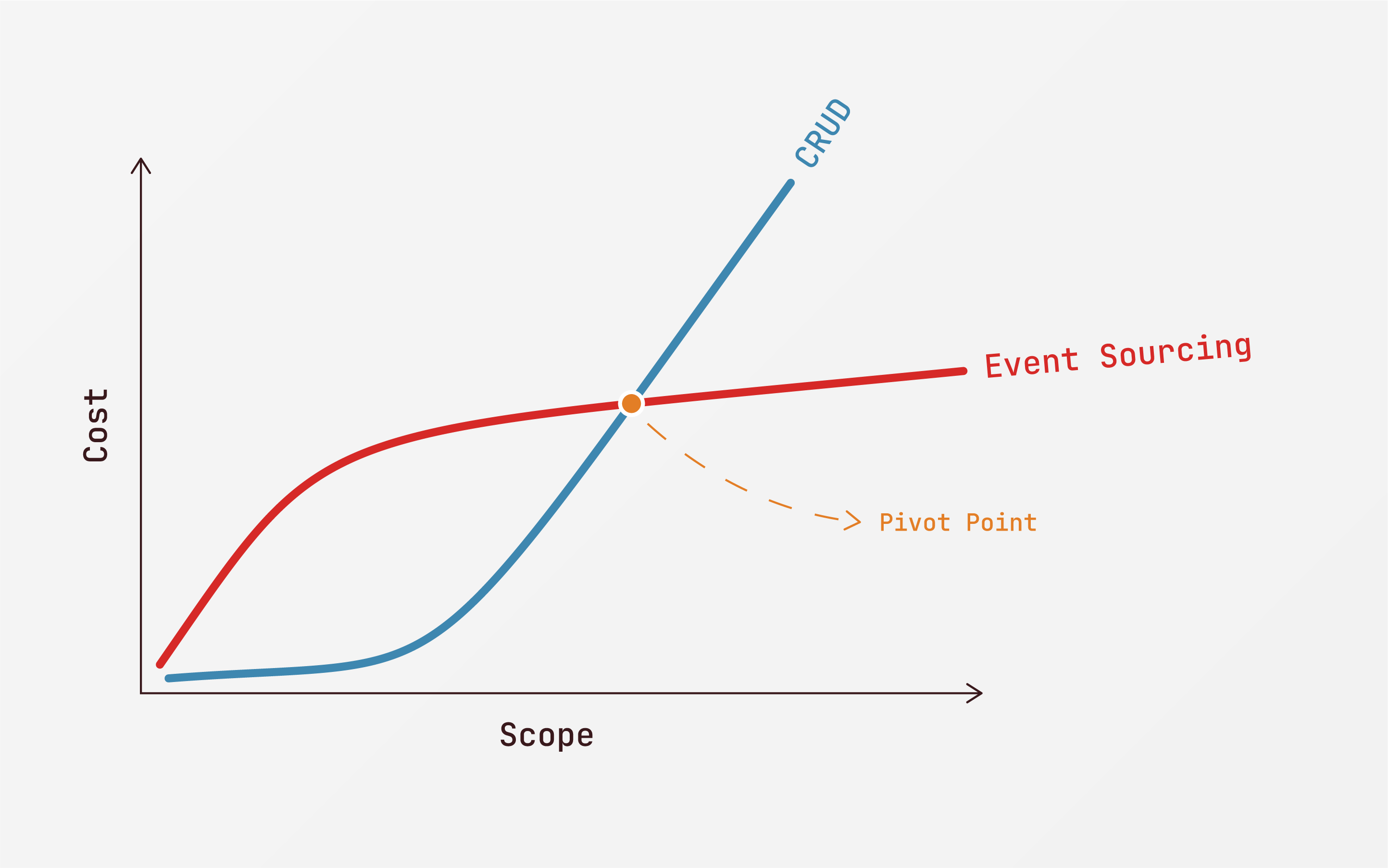

When I discuss event sourcing, people often assume that it comes with significant overhead, and that that overhead isn't justified in smaller projects. What they say is that there's some kind of pivot point, determined by the scope of the project, where event sourcing actually reduces costs, while in smaller projects it would introduce a cost overhead.

Something like this:

And, of course, this is an oversimplification, but it visualizes the argument very well: we should only use event sourcing in projects where we're sure it'll be worth it.

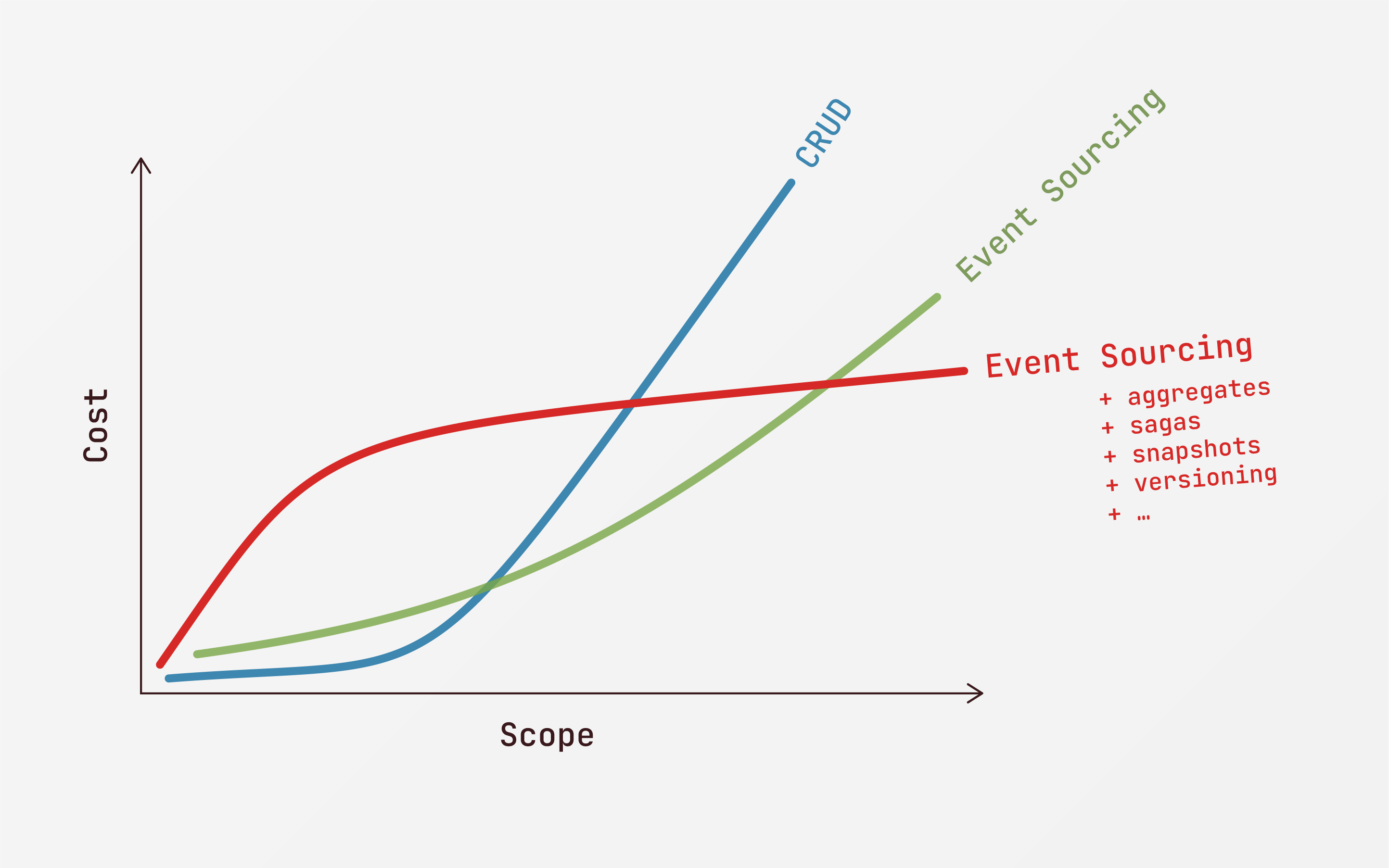

The problem with this statement is that it doesn't talk about just event sourcing, it talks about event sourcing with all its associated patterns as well: aggregates, sagas, snapshots, serialization, versioning, commands, …

Which is why I'd say our graph should look something more like this:

But does it even make sense to use event sourcing without the patterns that build on top it? There's a good reason why those patterns exist. That are the questions I want to answer today.

Here's Martin Fowler's vision on what event sourcing is:

"We can query an application's state to find out the current state of the world, and this answers many questions. However there are times when we don't just want to see where we are, we also want to know how we got there.

Event Sourcing ensures that all changes to application state are stored as a sequence of events. Not just can we query these events, we can also use the event log to reconstruct past states, and as a foundation to automatically adjust the state to cope with retroactive changes.

The fundamental idea of Event Sourcing is that of ensuring every change to the state of an application is captured in an event object, and that these event objects are themselves stored in the sequence they were applied for the same lifetime as the application state itself."

In other words: event sourcing is about storing changes, instead of their result. It's those changes that make up the final state of a project.

With event sourcing, the question of “is a cart checked out” should be answered by looking at the events that happened related to that cart, and not by looking at a cart's status.

That sounds like overhead indeed, so what are the benefits of such an approach? Fowler lists three:

- Complete Rebuild: the application's state can be thrown away and rebuilt only by looking at events. This gives lots of flexibility when you know changes to the program flow or data structure will happen in the future — I'll give an example of this later in this post, don't worry if it sounds a little abstract for now.

- Temporal Query: you can actually query events themselves to see what happened in the past. There's not just the end result of what happened, there's also the log of events themselves.

- Event Replay: if you want to, you can make changes to the event log to correct mistakes, and replay events from that point on to rebuild a correct application state.

There's one important thing missing in Fowler's list though: events model time extremely well. In fact, they are much closer to how we humans perceive the world than CRUD is.

Think of some kind of process of your daily life. It could be your morning routine, it could be you doing groceries, maybe you attended a class or had a meeting at work; anything goes, as long as there were several steps involved.

Now try to explain that process in as much detail as possible. I'll take the morning routine as an example:

- I got up at 5 AM

- Brushed my teeth — dental hygiene is important — and got dressed

- Went downstairs to make a coffee

- Went to my home office (with my coffee)

- Read up on mails

- Started writing this book

Thinking with events comes natural to us, much more natural than having a table containing the state of what's happening right now, as with a CRUD approach.

If there's already a “flow of time” to be discovered in something as mundane as my morning routine, what about any kind of process for our client projects? Making bookings, sending invoices, managing inventories, you name it; “time” is very often a crucial aspect, and CRUD isn't all that good in managing it since it only shows the current state.

I'm going to give you an example of how extremely simple event sourcing can be, without the need for any kind of framework or infrastructure, and where there's no overhead compared to CRUD, in fact, there's less.

I have a blog, this one; and I use Google Analytics to anonymously track visitors, page views, etc. Of course I know Google isn't the most privacy-focussed so I was tinkering with alternatives. One day I wondered if, instead of relying on client side tracking, I could just rely on my server logs to determine how many pages and which were visited.

So, I wrote a little script that monitors my nginx access log; it filters out traffic like bots, crawlers etc, and stores each visit as a line in a database table. Such a visit has some data associated with it: the URL, the timestamp, the user agent, etc.

And that's it.

Oh were you expecting more? Well, I did end up writing a little more code to make my life easier, but in essence, what we have here already is event sourcing: I keep a chronological log of everything that happened in my application and I can use SQL queries to aggregate the data, for example, to show visits per day.

Now, of course, with millions of visits over time, running raw SQL queries can become tedious, so I added one pattern that builds on event sourcing: projections; also known as the “read model” in CQRS.

Every time I store a visit in the table, I also dispatch it as an event. There are several subscribers that handle them, for example there's a subscriber that groups visits per day, it keeps track of them in a table with two columns: day and count. It's literally only a few lines of code:

class VisitsPerDay

{

public function __invoke(PageVisited $event): void

{

DB::insert(

'INSERT INTO visits_per_day (`day`, `count`)

VALUES (?, ?)

ON DUPLICATE KEY UPDATE `count` = `count` + 1',

[

$event->date->format('Y-m-d'),

1,

]

);

}

}Do you want visits per month? Per URL? I'll just make new subscribers. Here's the kicker though: I can add them after my application is deployed, and replay all previously stored events on them. So even when I make a change to my projectors or add new ones, I can always replay them from the point I started storing events, and not just from when I deployed a new feature.

This was especially useful in the beginning: there was lots of data coming in that were bots or traffic that weren't real users. I let the script run for a few days, observed the results, added some extra filtering, threw away all projection data and simply replayed all visits again. This way I wouldn't need to start all over again every time I made a change to the data.

And can make a guess how long it took to set up this event sourced project? 2 hours, from start to a working production version. Of course I used a framework for a DBAL and an event bus, but nothing specifically event sourcing related. Over the next days I did some fine tuning, added some charts based on my projection tables etc; but the event sourcing setup was absolutely easy to build.

And so, here's the point I'm trying to make: the event sourcing mindset is extremely powerful in many kinds of projects. Not just the ones that require a team of 20 developers to work on for five years. There are many problems where “time” plays a significant role, and most of those problems can be solved using a very simple form of event sourcing, without any overhead at all.

In fact, a CRUD approach would have cost me way more time to build this analytics project. Every time I made a change I would have to wait a few days to ensure this change was effective with real life visits. Event sourcing allowed me, a single developer, to actually be much more productive; which is the opposite of what many people believe event sourcing can achieve.

Now, don't get me wrong. I'm not saying event sourcing will simplify complex domain problems. Complex projects will take lots of time and resources, with or without event sourcing. Event sourcing simplifies some problems within those projects, and makes others a little harder.

But remember I'm not trying to make any conclusions about the absolute cost of using event sourcing or not. I only want people to realise that event sourcing in itself doesn't have to be extremely complex, and might indeed be a better solution for some projects, even when they are relatively small ones.

Greg Young, the one who came up with the term “event sourcing” more than 10 years ago, said that if your starting point for event sourcing is a framework, you're doing it wrong. It's a state of mind first, without needing any infrastructure. I actually hope that more developers can see it this way, that they remove the mental layer of complexity at first, and only add it back when actually needed. You can start with event sourcing today, without any special framework, and it might actually improve your workflow.

You'll notice that this book won't start with all those complex event sourcing patterns you might have heard about before and that might have made you take a step back from it. Instead, we're starting with the very essence of event sourcing, and looking at with world from an event sourced perspective. Only when we've got those fundamental basics down, we'll start worrying about applying patterns and principles to solve complex problems.